Improving outcomes in chronic disease management using nurse-led home telemonitoring

Alison Devitt CNC, MACN

“The telemonitoring nurse has become one of the pillars of my health, along with my general practitioner (GP) and cardiac nurse,” said Ron during an interview about his experiences participating in a six-month, nurse-led home telemonitoring trial.

Ron is a 52-year-old man living with multiple chronic conditions: congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and an anxiety disorder. Electronically recorded measurements of his BP, weight, Sp02, HR and one-lead ECG along with answers to questions about his symptoms are transmitted daily from his home to the nurse telemonitoring hub. The telemonitoring nurse then interprets the readings and responds further if indicated. If all is well, no further action is taken. Any readings that register outside Ron’s normal range prompt a follow up call for further assessment. Sometimes, all Ron needs is some health coaching. Occasionally consultation with his wider health care team is needed.

Ron was referred to the telemonitoring nurse by a hospital-based GP as his multiple chronic conditions impacted on each other resulting in frequent, unplanned hospital presentations. Later, Ron reported that prior to participating in the telemonitoring program he had a relatively low level of awareness about managing his multiple conditions and this led to him experiencing considerable anxiety. After six months of taking his telemonitoring readings on a daily basis, Ron showed significant improvement in self-management and health literacy with a subsequent reduction in anxiety, reduced social isolation and fewer hospital presentations. Most importantly for Ron was the impact on his quality of life. For the first time in many years he had the confidence to travel interstate to visit his son knowing that he could manage his health effectively while he was away.

Ron is, but, one of 25 participants over the age of 50 years living with at least one chronic condition, in rural NSW who participated in this nurse-led trial. The benefits of telemonitoring were most noticeable in participants whose chronic disease/s were more severe and in those who initially demonstrated a limited ability to effectively self-manage. These participants felt that the improvements to their capacity to manage their health issues more effectively were largely a result of the partnership they had formed with their trusted telemonitoring nurse, who they knew they could contact when needed. Ultimately, this helped them to both recognise and appropriately manage their symptoms and seek medical attention in a much timelier manner when they observed indications of an acute exacerbation. An additional benefit for several participants occurred when the telemonitoring data collected enabled the nurse to advocate for adjustments to their prescribed treatments (Burmeister et al., 2016).

In 2016, a Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) home telemonitoring research trial in which a nurse care coordinator managed a group of 100 chronically ill patients, reported similar findings. Importantly, these researchers were also able to demonstrate reduced costs overall, as a result of:

- Clinicians receiving early warning of deterioration enabling early intervention

- Improved self-management

- Reduction in unplanned hospital admissions

- Reduction in length of hospital stay (Celler et al., 2016, p. 17)

The emerging evidence demonstrating the multiple benefits of home telemonitoring, as described in the CSIRO trial and in this study, is beginning to influence Australia’s health care strategies. Last year in NSW, the Ministry of Health (2016) released a telehealth framework and implementation strategy for 2016-2021. This has exciting implications for nursing as a profession, with opportunities to contribute to advances in health care delivery.

Although home telemonitoring is well-established in countries such as the US, it is still in its infancy in Australia. There is much to be done to perfect the use of this technology to enable effective integration within the wider health system. Our nursing team involved in Ron’s care and that of the other participants in the study, have learned much from this pilot project. I have chosen five particularly pertinent learning points that I would like to share with you.

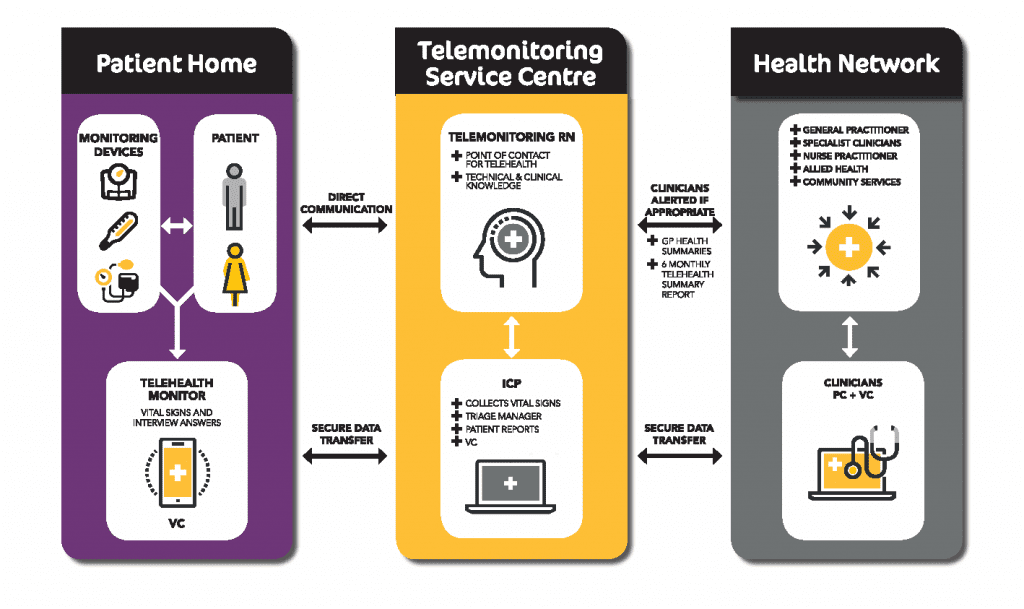

- The telemonitoring nurse as clinical care coordinator was critical to the success of the service. The nurse-led home telemonitoring model used in this trial and which is visually depicted below (Image 1), shows the centrality of the nurse in assessment, education of patients and referral to other members of the health team, including the patients’ GP and a range of community service providers. In this model, the nurse acts as a gateway for the collection and sharing of information, as well as a central point of contact for the patient and health team.

Image 1 – LiveBetter Community Services Nurse-Led Home Telemonitoring Model

- For a nurse to successfully undertake the telemonitoring role it requires the capacity for advanced nursing practice in the care of people with complex health care needs. Some of the specific capabilities needed include: well-developed interpersonal communication skills; an ability to work collaboratively with patients, carers and the interprofessional health team; health coaching skills; high assessment confidence and; a well-developed capacity for clinical reasoning in combination with confidence in the use of telemonitoring technology. These requirements are consistent with previous research identifying the competencies required for nursing telehealth activities (van Houwelingen et al. 2016).

- In this trial, a frustrating barrier to effective interprofessional collaboration occurred when GP participation was poor. Previous studies that shown GPs’ scepticism and reluctance to participate in similar activities related to personal barriers, reimbursement barriers and clinical workflow barriers (Brooks et al., 2013; Wade et al., 2014). Optimal outcomes in telehealth occur when services are delivered as part of team care and when there is effective communication between the team (NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2015). We need to discover ways to both increase involvement of GPs and other health providers and to develop effective collaborative relationships.

- Implementation of telemonitoring is newly emerging as part of health care service delivery in Australia. Forming a “community of practice” for health professionals involved in this area of health care will assist cross-organisational learning, facilitate sharing of solutions for common problems and enable development of health care policies and clinical practice guidelines specific to this evolving area of practice (Wade et al., 2016).

- Current telemonitoring technology relies heavily on interpretation of vital signs for assessment of the person. A reliance on vital signs alone as indicators of a deteriorating patient has been shown to produce suboptimal outcomes (Chua & Liaw, 2015). Multiple opportunities exist for experienced nurses to actively engage with designers of telemonitoring technology. Combining the assessment capacity of current technology with nursing processes is one of many ways in which the functionality of these technologies could be significantly improved.

At a time when the health care profession is being increasingly challenged by the complexities of a growing number of people living with multiple chronic conditions, home telemonitoring led by nurses in advanced clinical care coordinator roles is being recognised as an approach that improves patient outcomes (CSIRO, 2016). This model of care offers financial savings to the health care budget. However, if it is to find a sustainable place in Australia’s health care system, financial support from the government (e.g. with MBS items specific for the needs of telemonitoring services) will be required. Nursing, as the largest group of health professionals, is well placed to advocate for these changes. May Ron’s words be a challenge for us to embrace technology, as we herald the way to an improved quality of life and a better health care experience for people living with chronic and complex conditions.

Note: participant name has been changed for the sake of anonymity.

Acknowledgements: Associate Professor Rachel Rossiter

References:

Burmeister, OK, Ritchie, D, Devitt, A, Chia, E, & Dresser, G, 2016, ‘Evaluating the social and economic value of the use of telehealth technology to improve self-management by older people living in the community, paper presented at the Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Wollongong, Australia, 5-7 December, accessed 12 May 2017, <https://business.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@bus/documents/doc/uow223920.pdf>

Brooks, E, Turvey, C, & Augusterfer, EF, 2013, ‘Provider barriers to telemental health: obstacles overcome, obstacles remaining’, Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, vol.19, no.6, pp. 433-7

Celler, B., et al., 2016, Monitoring of Chronic Disease for Aged Care: Final Report 2016, Australia: CSIRO

Chua, WL, & Liaw, SY, 2015, ‘Assessing beyond vital signs to detect early patient deterioration’, Evidence-Based Nursing, published online doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102092

Ministry of Health, 2016, NSW Health Telehealth Framework and Implementation Strategy 2016-2021’, North Sydney: Ministry of Health, accessed 13 June 2017, <http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/telehealth/Publications/NSW-telehealth-framework.pdf>

Wade, V, Eliott, JA, & Hiller, JE 2014, ‘Clinician acceptance is the key factor for sustainable telehealth services’, Qualitative Health Research, vol. 24, no. 5, pp.682-694

Wade, VA, Taylor, AD, Kidd, MR, & Caraty, C, 2016, ‘Transitioning a home telehealth project into a sustainable, large-scale service: a qualitative study’, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 16, No. 172, pp. 183-192

van Houwelingen, CTM, Hoerman, AH, Ettema, RGA, Kort, HS & Cate, OT, 2016, ‘Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: a Delphi-study’, Nurse Education Today, Vol. 29, pp. 50-62