You can read Part one of Nursing in the 1918 pandemic on our NurseClick blog.

By Ruth Rae, FACN, PhD.

In early 1916 Australian soldiers were divided into two divisions, one remained in Egypt and the other went to Europe.[1] Nellie Miles-Walker was transferred to England with nurses from 1 and 2 Australian General Hospital (AGH) who would provide nursing care for soldiers on the Western Front in France and Belgium. She was appointed Matron of 3 Australian Auxiliary Hospital (AAH) in Dartford, Kent (Oct 1916) while awaiting overseas placement. This came in July 1917 when Miles-Walker was appointed Matron of 5 British Stationary Hospital (BSH), Dieppe. One of her Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) nurses, Staff Nurse Leila Brown found it to be ‘…another British Hospital staffed by Australian sisters. It was a small Stationary Hospital and took mostly local sick and injured – it being the principal port for the landing of war materials, there were frequently accidents. Here we were billeted in a charming house and had everything one could wish for to make life happy. We had a ‘Tommy’ as cook and you could not have recognised army rations in the excellent dinners he served up every night. Here for the first time I worked the hours generally set in Australian Hospitals … one whole day per week off duty, and alternate long and short days. There was a golf course nearby and I was able to play quite often, there was also a tennis court built us by a French Baron who owned a house close to ours and if we brought visitors to the house … Miss Mills-Walker [sic] who was Matron welcomed them and made the atmosphere quite that of a home’.[2] Unfortunately, this idyll did not last long.

The most challenging situation for Matron Miles-Walker occurred when she was matron of 3 AGH in Abbeville during the German advance in early 1918. German General Ludendorff wanted to avail himself of the opportunity for a breakthrough on the Western Front which the withdrawal of Russia from the allied forces presented. The entry of the USA into the war and the helplessness of the Austro-Hungarians (who were enduring a famine) were putting pressure on the German offensive strategies.[3] Finally, when the German Army advanced, Matron Miles-Walker’s 1,500-bed general hospital was turned into a 2,000 bed CCS practically overnight. It was in March 1918, that she received orders that 3AGH was to act as a CCS as the enemy advanced to Amiens – an important strategic location for the allies. No 3 AGH was inundated with 1,800 casualties.[4] Matron Miles-Walker kept in contact with her nurses, who were constantly being sent to the forward areas to work in the CCS.[5] The nurses found this time particularly difficult as they were bombed each night, so rest was near impossible. AANS nurses like Mary Dwyer and Anne Donnell were stationed in CCSs on the Western Front and endured constant night air-raids where they ‘…thought our last hour had arrived’.[6] Later, Anne Donnell, while on leave in London for ‘debility’, makes the simple statement that ‘…I long sometimes to breathe again’.[7] After the war May Tilton ‘… felt something happen to my brain. It seemed to expand, as though a tight band was suddenly lifted from it. I will never forget the experience or the relief’.[8] Both Tilton and Donnell had served with Nellie Miles-Walker at a time of heightened angst when she dealt with the avalanche of casualties with a staff of one head sister, 15 sisters and 24 SNs.[9]

The approach of the Germans was a terrifying prospect for the nurses. They were, as ever, reluctant to leave their patients, who dreaded the idea of being captured. The CCSs and AGHs began to meld during the shelling at Hazebrouck. Mary Dwyer (AANS) recorded that the order came for their ‘…immediate evacuation, we left about 2 o’clock by a London bus, luggage inside and Sisters on the top. It was a pathetic sight to see the civilians carrying their personal belongings in a barrow or bicycle and leaving their homes’.[10] During the retreat, nurses were supposedly ‘…evacuated 25 at a time to Hardelot and Boulogne’ but the continual bombing of infrastructure and the close proximity of the Germans created an atmosphere of organised chaos.[11] Matrons Miles-Walker and Grace Wilson did not lose any of the 3 AGH nurses during the retreat, although one BCCS was captured; patients and medical officers were taken as POWs.[12] The number of soldiers who died during the retreat is inestimable but the noise, pain, fear and absence of a normal hospital infrastructure compounded the misery of their deaths.

Finally, in October 1918, Matron Miles-Walker was safely back in London but the workload of her nurses was not relieved as the war wounds were replaced by the enormous numbers of influenza victims. It was at this time she herself became ill. She died suddenly.

Her death was keenly felt and Sister Anne Donnell who had experienced her kindness recorded we ‘…have just lost one of our Matrons from this terrible influenza – Miss Myles-Walker [sic]. She was such a fine woman, and all we Nursing Sisters abroad have indeed lost a friend. Matron and I have just returned from her funeral at Sutton Veny. It was a military funeral and very representative. The coffin was draped with the Union Jack, but when I saw her red cape and white cap lying on top of the beautiful wreath of flowers it fairly broke me up’. The Anglican burial at Sutton Veny churchyard was well attended by her colleagues and when the armistice was declared Sister Donnell could not shake a heavy heart. She confided in her matron that she would give anything to feel happy and the matron empathetically replied that she understood because ‘…we must not forget in our joy to think of others in their sorrow’.[13]

Nellie Miles-Walker was the most senior AANS nurse to die and the tragedy of her death after four years of continuous service, within a fortnight of the armistice, was apparent – especially to her bereaved mother. Louisa Walker was unable to claim her daughter’s personal possessions without first proving her relationship, because at the time of Nellie’s enlistment Louisa had been ill and her son, Albert, was the designated next-of-kin. The correspondence on this subject between the army and Louisa Walker is both extensive and heart-wrenching. A particularly poignant remark displays the level of distress experienced by the grieving mother who ‘…was in close correspondence all those four years with my beloved daughter. Cheering and helping her and now to think there should be a doubt about me being her “Mother” … the very smallest trifle belonging to my child is most precious to me, and I wish no other hand to touch it first. This may sound sentimental but if you have ever loved anyone deeply you will understand it’.[14] An experienced compassionate and competent nurse, Nellie was also the youngest child of Louisa, dying from the ‘flu’ just a few weeks prior to her fortieth birthday.

The letters of Louisa Walker brings the grief felt by those who waited at home for more than four long years into sharp historical focus. Little did the world realize the influenza pandemic was about to ravage those waiting at home as well as the exhausted soldiers and nurses who thought they had survived the hell of the First World War only to be faced with more death. To be robbed of the much anticipated reunion at the last moment reminds us that the millions of dead soldiers, nurses and civilians left behind a world filled with heart-breaking grief.

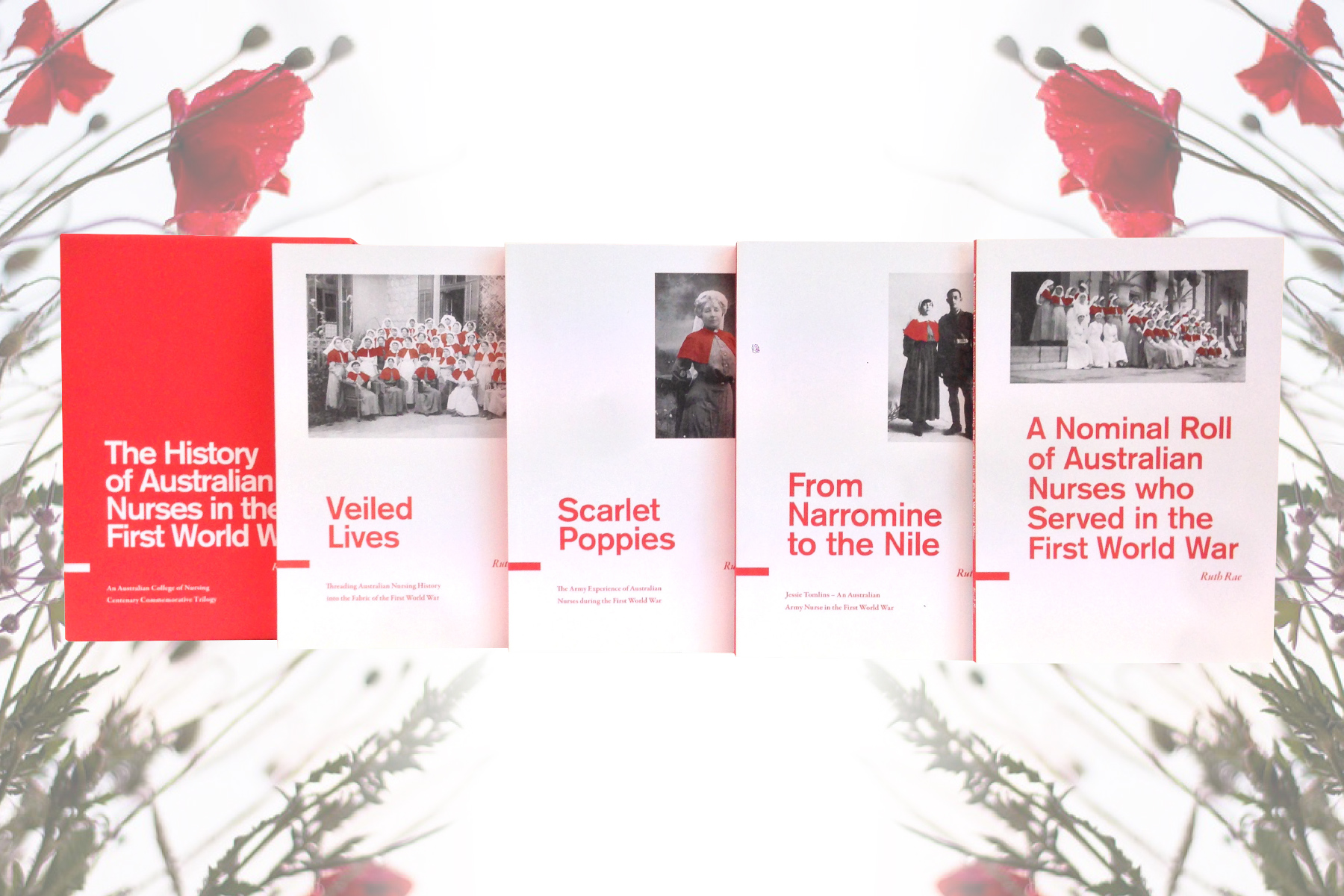

Note: The research and material of this biography is taken from previous research undertaken by the author, Dr Ruth Rae FACN, published in Scarlet Poppies and Veiled Lives (books two and three of The History of Australian Nurses in the First World War (the Trilogy).

[1] C. E. W. Bean, Anzac to Amiens (5th ed.), Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1968, pp.192-3; A. J. Smithers, Sir John Monash: A Biography of Australia’s Most Distinguished Soldier of the First World War, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1973, pp.139-140.

[2] A. G. Butler The Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services in the war of 1914-1918: Special Problems and Services, Vol 3, Australian War Memorial Canberra, 1943, p.576; Narrative, Staff Nurse Leila Brown, Records of A. G. Butler: Official Historian of Australian Army Medical Services – Nurses’ Narratives; R. Goodman, Our War Nurses: The History of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps 1902-1988, Boolarong Publications, Brisbane, 1988, p.58.

[3] Bean, Anzac to Amiens, pp.398-400,408-09;

[4] M.Barker, Nightingales in the Mud, Allen and Unwin, Sydney,1989, p.140.

[5] Sister Evelyn Davies cited in Barker, Nightingales in the Mud, p.115.

[6] Narrative, Sister Mary G.Dwyer, Records of A.G.Butler Historian of Australian Army Medical Services –

Nurses’ Narratives. .

[7]A. Donnell, Letters of An Australian Army Sister, Angus and Robertson Ltd, Sydney, 1920, p.253.

[8] May Tilton, The Grey Battalion, Angus and Robertson Limited, Sydney, 1933, p.293.

[9] ‘Report on Nursing Staff, April 1918’ by Principal Matron Grace Wilson, Third Australian General Hospital, Records of A. G. Butler: Official Historian of Australian Army Medical Services, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

[10] Narrative, Mary Dwyer, Records of A. G. Butler: Official Historian of Australian Army Medical Services

– Nurses’ Narratives.

[11] Narrative, Edith E. Simpson, Records of A. G. Butler: Official Historian of Australian Army Medical

Services – Nurses’ Narratives.

[12] .Barker, Nightingales in the Mud, p.113.

[13] Donnell, Letters of An Australian Army Sister, p.273.

[14] Correspondence, Louisa Walker to Staff Officer Base Records, 28 June 1919, in Jean Nellie Miles-

Walker Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers. The service record of Miss Jean Nellie Miles-Walker includes official documents which list her mother as next-of-kin while others list her brother as next-of-kin; correspondence in Jean Nellie Miles-Walker Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers.