By Ruth Rae, FACN, PhD.

Today Australian nurses are facing the challenge of saving lives amid an influenza pandemic on home soil. Any suggestion they have let their profession down when they contract the virus defies all logic. They are the frontline defence and they put themselves at risk for the benefit of their patients and the wider community. In 1918 their predecessors dealt with a similar virus during the most brutal war of the twentieth century while overseas. These nurses trained under the Nightingale System of nurses training in civilian hospitals, qualified with the Australasian Trained Nurses’ Association (ATNA) which enabled them to immediately volunteer with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) when war was declared in 1914.[1] One such nurse was Nellie Miles-Walker from Tasmania.

Jean Nellie Walker joined the AANS during peacetime as a reserve (1906) and within three years she was appointed Principal Matron (PM) of the Tasmanian contingent (6 Military District). She hyphened her surname and used her middle name to differentiate herself from another Tasmanian nurse who also enlisted with the AANS, Jean Roberto Walker.[2]

PM Nellie Miles-Walker was born 16 November 1878 at River Forth (now known as Forth) near Port Sorrell in northern Tasmania, daughter of Alfred and Louisa. Her family life was not atypical at this time and within eleven years of marriage Louisa and Alfred had nine children, Jean Nellie being the youngest. Her father died when she was just three years old and her bond with her mother was close and life-long. Louisa was a widow with many dependent children but her youngest was privately educated until she enrolled at the Collegiate School in Hobart (1893). In 1906 she completed a three-year nurse training course at the Hobart General Hospital and joined the AANS the same year. She remained with her training hospital until 1908 when she began private nursing, a popular career choice at the time. In 1913 she completed six months’ midwifery training at the Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, and then served as matron of private hospitals at Tallangatta, Victoria and Darlinghurst, Sydney.[3]

When war was declared, nurses were no longer part of a reserve but enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). They were required to furnish references from doctors and did not necessarily hold the same rank. Dr Sheldon scratched a note on a letterhead ‘Molong Private Hospital, Forbes Street, Darlinghurst’ which, in essence, stated that Miles-Walker was ‘…quite competent in all branches of nursing (being in charge of above hospital)’. She was about to prove she was extremely competent in military nursing. AANS nurses, like their soldier counterparts, had to complete a last will and testament prior to embarkation. The norm was that a male next-of-kin was nominated over a female relative and Nellie designated her brother, Albert.[4]

Principal Matron of the AANS was Nellie Gould who led the first contingent of nurses who were assigned to the AIF transport ships. The destination was expected to be England but the alliance of Turkey with enemy resulted in Egypt being the first theatre of war for the nurses. PM Gould recorded ‘…on 29th September, 1914, Principal Matron Gould, EJ, Matron Johnston, J Bligh, Sisters Frater, P., Kellett, AM, Twynam, and the Matron of the Tasmanian AANS who happened to be working on Reserve in Sydney, … Miss Walker, J., were detailed for duty on Transport “Euripides”.[5] A Principal Matron of the AANS reserve was now a Sister of the AANS (AIF). The rank of the nurses during wartime started with Staff Nurse (ATNA qualified but not part of the AANS Reserve); after twelve months service and support from their matron they were promoted to Sister. The decision to enable a nurse to rise to assistant Matron or Matron was at the discretion of the Principal Matron.

On arrival in Egypt, the nurse leaders were required to transform hotels, old army barracks and even skating rinks into hospitals. The first battle in April 1915 was yet to be planned but Sister Miles-Walker and her colleagues knew the importance of preparations. By the time Staff Nurse Moreton arrived in early 1915 she was sent to the Ghezireh Palace Hotel, now 2 Australian General Hospital (2AGH) where she found Matron Gould to be a ‘…wonderful matron, such a splendid manager’. The workload during the Dardanelle campaign was extraordinary for these civilian trained nurses who quickly adjusted to military nursing. SN Moreton found that the staff at 2AGH are ‘… very good to the patients here. Since we came we have admitted over 800’ in the first three weeks of her service.[6] The AANS nurses adapted to the appalling wartime conditions by falling back on their inherent professionalism but ‘…those of the wounded who knew them previously were shocked at the change which the strain had produced in them’. In the main, the nurses focused on their nursing but some found the military regulations irksome. Sister Haynes preferred to work at 2 AGH than at any other hospital but she found the rules and regulation of the army ‘…quite mad’, especially during the Egyptian summer when the ‘…matron has a fit when she sees us without our capes’– although it was not long before the Australian nurses wore their scarlet capes with the same pride as the Australian soldiers wore their slouch hats.[7]

The competence of Sister Miles-Walker was apparent to PM Gould who appointed her Acting Matron of 1 Australian Stationary Hospital (1ASH), Ismailia (Feb-Aug 1916). The hospital was a former French convent located north of the Suez Canal between Suez and Kantara. While 1 ASH was not particularly busy until the Battle of Romani in early August 1916, the location of the hospital and the extreme climate were enervating for the nurses and many suffered from general debility. The term ‘general debility’ was widely used to describe nurses who were basically exhausted. It was also a pseudonym for PTSD although the condition was unheard of at this time. A diagnosis of ‘Shell Shock’ was reserved for soldiers who had been in the thick of battle but nurses who witnessed the results of such battles were often traumatized.[8] Fortunately, the staff and patients were served well by Miles-Walker who was universally liked but also respected.

On arrival in Egypt, Beatrice Watson (Melbourne Childrens’ Hospital) was admitted to 1 ASH within a month (28 February 1916) for influenza and like all nurses who are ill, received the special attention of the matron. The matron was considered loco parentis to her nurses. At the same time, Mary Stafford (1AGH) also succumbed to influenza but fortunately, the severity of influenza varied considerably and they both made a good recovery. However, Beatrice Watson was readmitted on 1 June and died the next day of ‘cerebral’. Her medical record initially stated she ‘…died of disease (abscess of brain)’ but the additional diagnosis of ‘…cerebral haemorrhage’ was added later. Diagnosis was not an exact science at this time but there was a tendency for those nurses who had ‘flu’ to later die of other causes. Matron Miles-Walker, no doubt, felt the death of one of her nurses keenly and the letter she wrote to her parents would have reinforced her sadness. The funeral of Beatrice Watson was attended by her AANS colleagues and her soldier patients. Her grave can be found in the Ismailia War Cemetery and is dominated by a large cross, but gives very little away about the woman who rests there, except that she belonged to the Church of England and was an army nurse.[9] Nurses were adjusting to grief on a grand scale but the loss of a colleague, who could not be mourned by her family, never became commonplace.

Keep an eye out on NurseClick next week for the second and final instalment of Nursing in the 1918 Pandemic.

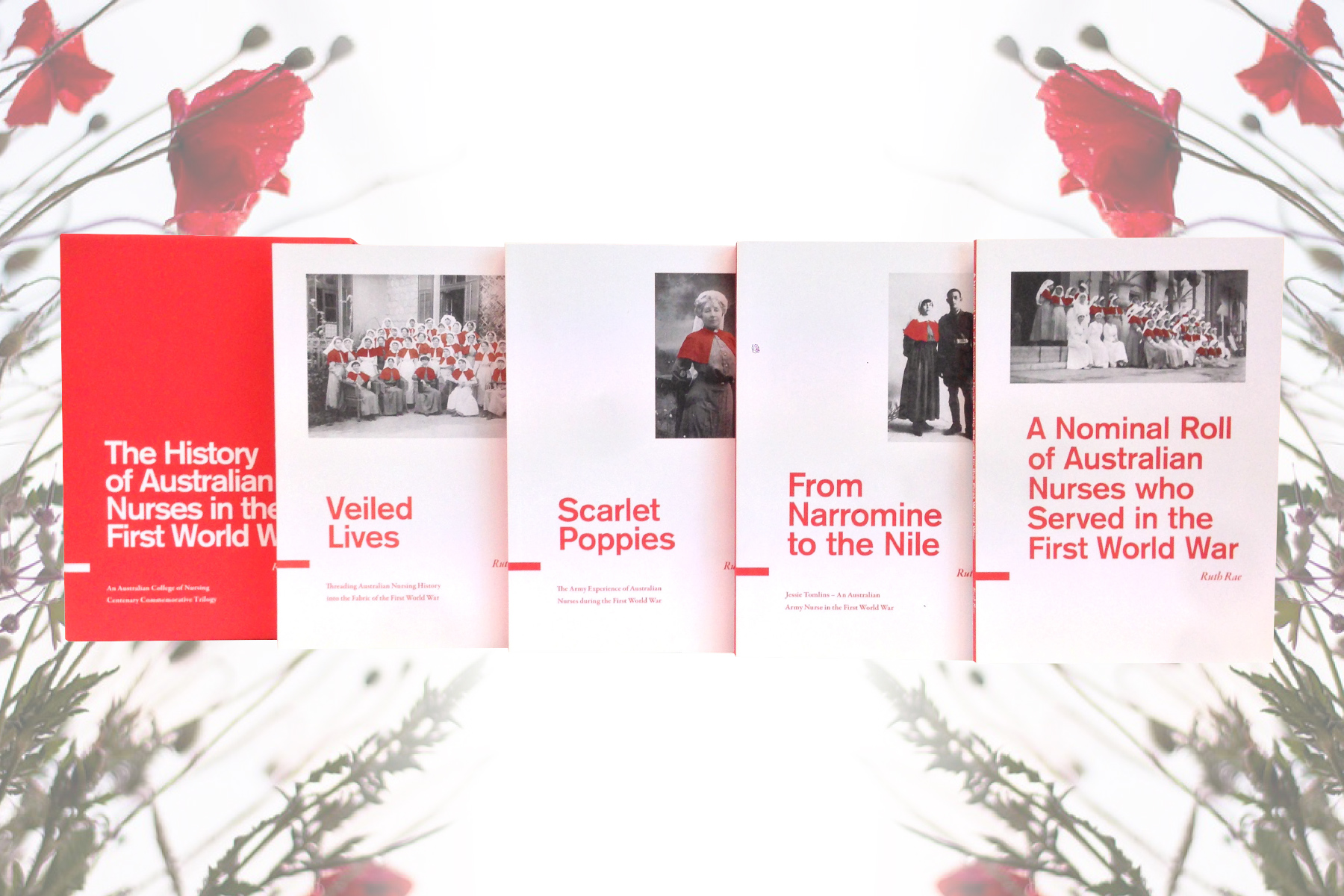

Note: The research and material of this biography is taken from previous research undertaken by the author, Dr Ruth Rae FACN, published in Scarlet Poppies and Veiled Lives (books two and three of The History of Australian Nurses in the First World War (the Trilogy).

[1] Military Forces of the Commonwealth, General Order no 269, 1903 cited in J.Bassett, Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford

University Press, Melbourne, 1992, pp.24 & 26.

[2] Nellie Miles-Walker, Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers, Service Record, Australian

Archives, Canberra, 1919 (http://naa12.naa.gov.au/scripts/Imagine.asp); NSW Pioneers Register Index

1788-1888, Births, Deaths and Marriages; Jean Roberto Walker, Military Forces of the Commonwealth

Papers, Service Record, NAA, Canberra.

[3] J Bassett ‘Walker, Jean Nellie Miles (1878-1918)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 12,

Melbourne University Press, 1990, p.362; NSW Pioneers Register Index

1788-1888, Births, Deaths and Marriages.

[4] The service record of Miss Jean Nellie Miles-Walker includes official documents which list her mother

as next-of-kin while others list her brother as next-of-kin; Correspondence in Jean Nellie Miles-Walker

Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers.

[5] Gould, E. J., ‘New South Wales assistance asked in connection with the collection of historical material

for Australian Army Nursing Service, AIF. Report by Miss EJ Gould’ (Gould Report) AWM 4364/34/6,

Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1933, p.2.

[6] Correspondence, L. G. Moreton, 6 August 1915, 2 AGH, Cairo, Egypt in Typed Extracts of Correspondence

at AWM File No. 12/11/1398 – 2 DRL 97, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, p.2; J. Bassett,

‘Walker, Jean Nellie Miles (1878-1918)’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 12, Melbourne

University Press, 1990, p.362.

[7] Olive Haynes, diary entry, 30 September 1915 in M. Young (ed), We Are Here, Too: The Diaries and

Letters of Sister Olive L. C. Haynes November 1914 to February 1918, Australian Down Syndrome

Association Inc, Adelaide, 1991, pp.33 & 47.

[8] Research relating to this topic has been previously published in R. Rae, ‘An historical account of

shell-shock during the First World War and reforms in mental health in Australia 1914-1939’, International

Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 2007, 16: 266-273.

[9] Beatrice Middleton Watson, Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers [online 22 July 2006];

Digger–Pioneer Index.Victoria 1836-1888[ online 18 August 2006]; Mary Florence Stafford, Military Forces of the Commonwealth Papers; AWM Roll of Honour: http://

www.awm.gov.au/database/roh.asp.AWM Nominal Roll: http://www.awm.gov.au/database.