On Sunday, 14 May 2023, nurses and military personnel across Australia will come together to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the sinking of the Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur in World War II.

The hospital ship, carrying 332 civilians, injured personnel and hospital staff, was travelling off the coast of Brisbane, Queensland, when it was torpedoed by enemy forces and sunk. As the Centaur was bombed in the middle of the night, many of the hospital staff and civilians were asleep and did not have a chance to flee.

268 people died in the sinking of the AHS Centaur, including 11 nurses. Only one nurse, Sister Ellen Savage GM, survived.

The ship was considered lost off the coast of Brisbane for many years, with the wreckage found in December 2009.

In the week of the 80th anniversary, we revisit the sinking of the hospital ship, the nurses who died, and the Australian response.

The sinking of the AHS Centaur

A known hospital ship, the AHS Centaur was travelling from Sydney back to Papua New Guinea to deliver the 2/12th Australian Field Ambulance and evacuate more injured servicemen and civilians when it was struck by a torpedo and sunk. Service ship bombings were common to easily target hundreds of people, but hospital ships were considered a protected class under the Geneva Convention and were to be avoided.

Despite clear markings of a hospital ship, the AHS Centaur was targeted and eliminated.

Due to the timing of the bombing – reports say approximately 4:10am – many staff and civilians were asleep or resting and had little to no time to evacuate or escape. Despite being relatively close to land, the ship sank in three minutes and was not able to put out a distress signal. Evacuees could not get off the ship before it sunk, and many died in the inferno or through concussion.

The ship was carrying more than 300 people, mostly doctors, nurses, army medics from the 2/12th Australian Field Ambulance, injured and recovering patients, and ship operators.

Eighty per cent of the crew did not survive.

Image: the AHS Centaur with its signature cross to indicate it was a hospital ship. Source: Australian War Memorial

The nurses who died

Twelve nurses were on board the AHS Centaur when it was travelling past Brisbane that night.

Military nurses served in World War II through the Australian Army Nursing Service. It was the only way women could serve in the World Wars and they were a proud, skilled, and underrecognised, team.

When the AHS Centaur was bombed, many of the nursing sisters were asleep and did not have a chance to escape.

Two nurses managed to escape the flaming wreckage and dived into the water. One of these was Sister Ellen Savage GM, who ended up surviving the tragedy.

Sister Savage, after being safely evacuated from the wreckage, was reported to say that she woke up to a loud bang and flames everywhere. She grabbed cabinmate Sister Myrtle Moston and ran, eventually making it off the side of the ship and into the water. Unfortunately, Sister Moston was struck by falling timber and drowned.

Eleven nurses died in the sinking. They were:

- Matron Sarah Anne Jewell

- Captain Sister Margaret Lamont Adams

- Sister Mary Hamilton McFarlane

- Captain Eileen Mary Rutherford

- Sister Wendy ‘Jennie’ Walker

- Sister Doris Joyce Wyllie

- Sister Myrtle Moston

- Sister Alice Margaret O’Donnell

- Sister Evelyn Veronica King

- Sister Edna Alice Shaw

- Sister Helen Haultain

Many of their bodies were never found.

Sister Savage was awarded a George Medal for her bravery and resilience in providing medical care, boosting morale and courage in the 36 hours survivors had to wait for rescue.

The reaction

It was the first experience for many Australians of the horrors of war upfront and personal, with the bombing happening right off the coast of Brisbane. TVs and instant communication were not developed yet, and many felt fear of the war so close to their homes.

The reaction was intense and fuelled by outrage, particularly at the bombing of a hospital ship. Australians broadly valued the protected status of health workers and the critical work they did. To see health workers targeted on their doorstep was shocking and an affront to their values.

After outcry, the Australian and British Governments petitioned Japan to release the people responsible so they could be tried for war crimes. The eventual probable identity of the submarine was not made available until the 1970s.

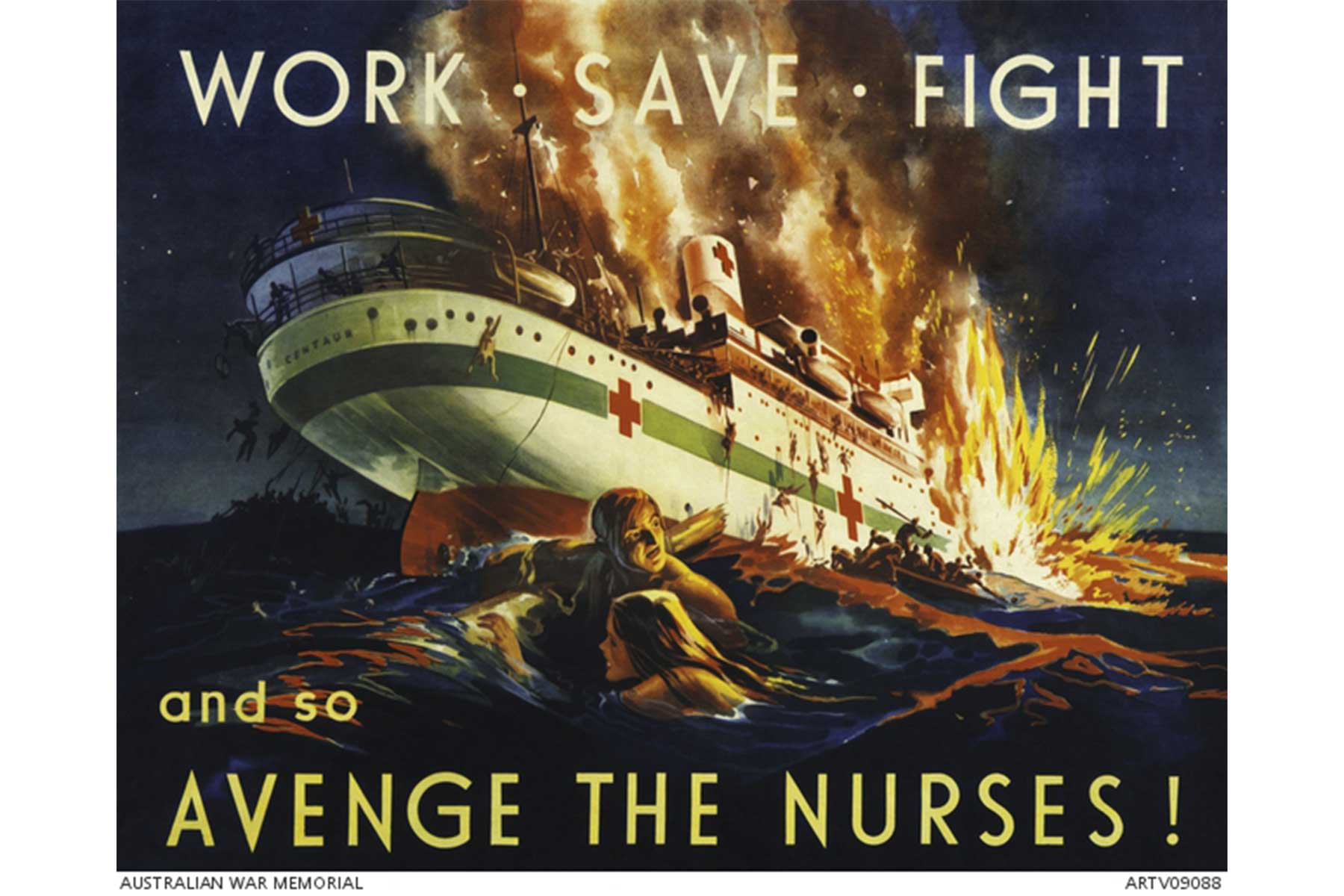

The Australian Government used the sinking of the AHS Centaur to stimulate recruitment, with propaganda pieces of the attack on the hospital ship. The words ‘WORK. SAVE. FIGHT. AVENGE THE NURSES’ were donned across Australia, calling for more servicemen to join the war.

Image: Propaganda images used the sinking to call for greater action on the war, emphasising the need to avenge the nurses. Source: Australian War Memorial

In 1948, nurses in Queensland established the Centaur Memorial Fund for Nurses to provide awards and scholarships for future generations of nurses. The Fund is still running today.

It was not the first attack on the Australian Army Nursing Service, but Australians would have to wait until after the war ceased in 1946 to learn of the other war atrocity. Lieutenant Colonel Vivian Bullwinkel AO, MBE, ARRC, ED, FNM, FRCNA was the sole survivor of the Bangka Island massacre in 1942, where 22 nurses were marched into the water and shot after having surrendered.

LTCOL Bullwinkel was made a prisoner of war, and so was not able to share this incident until after her release at the end of the war.

Find out more about the sinking of the AHS Centaur at the Australian War Memorial.

The Australian College of Nursing is dedicated to ensuring that nursing history is alive and nurses who paid the ultimate sacrifice to serve in war are remembered. If you are interested in learning more, the ACN History Faculty is conducting a webinar with everything you need to know about the sinking and the effects on nurses. Register today and join us in commemorating nursing history.